Recreational Flying, also known as Sports flying, is a sub category of General Aviation which is more lightly regulated than the rest of General Aviation. The logic is that the the aircraft are lighter and less complicated (not always the case), so therefore the risk should be lower.

Generally speaking, Recreational aircraft are uncertified, the pilots receive less rigorous mandatory training, and medical requirements can be as little as a driving license, or nothing, depending on the country.

Recreational flying, by it’s construct, is predominately a national affair, and hence, the regulation that applies to it can be radically different depending on the country. This is a major difference from the rest of General Aviation (and Civil Aviation) which has been aligned as much as possible since the Chicago Convention of 1944, with the goal of enabling easy international transit.

Heavy regulation has been the biggest obstacle to Innovation in General Aviation. Small companies have not been able to afford the cost of certifying new designs. That is why when it comes to certified aircraft, you see everyone flying 70 year old Cessna’s and Piper’s with pre World War 2 engine technology.

Recreational Flying has become the big compromise with national regulators allowing adoption of Industry consensus rather than direct regulatory oversight. The goal has been to maintain an Acceptable level of safety. Europe has been the pioneer for factory built aircraft, especially in Germany and the Czech republic. The USA has led in the amateur kit built aircraft market.

Enough of an introduction and generalities, let’s dig into the differences EASA and the FAA have taken to regulate Recreational Aircraft.

A widely different Definition of an Ultralight

The FAA considers Ultralights as vehicles and not aircraft. They are described under AC Part 103 regulation and are treated more like bicycles than aircraft that they do not require Airworthiness Certificates, Registration or Licensing.

They must only be

- operated by a single occupant and weigh less than 70 kg if unpowered

- If powered weigh less than 115 kg, not travel faster than 55 knots, not stall faster than 25 knots and carry more than 19 liters of fuel.

EASA considers Ultralights as Non-EASA Annex 1 aircraft that fall under National member state supervision. EASA Basic regulation (EU) 2018/1139 states that these aircraft must meet the following requirements:

- Stall speed not exceeding 35 knots

- no more than two seats

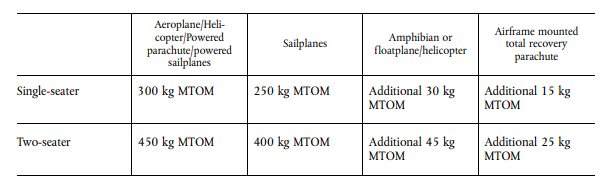

- MTOW not exceeding the below weights

An amendment in the above referenced regulation allows member states to opt-out of EASA regulation of 450 – 600 kg aircraft. In practice this meaning that member states if they opted-out would be permitted to allow Ultralights in their own territory up to 600 kg.

This was very exciting news in Europe as many very capable aircraft that have been operating in the USA as 600 kg LSA have been forced to operate at an unrealistic 450 – 475 kg in Europe. (Most two seaters have an empty weight around 300 kg allowing only 175 kg for occupants and fuel)

Similar LSA Definition but very different approaches to Certifying

Both EASA and the FAA have a definition of Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) that is very similar, but how they have chosen to certify the aircraft is completely different. Firstly let’s take a look at the definition.

EASA Definition for Light Sport Aircraft

- A Maximum Take-Off Mass of not more than 600 kg

- A maximum stall speed of not more than 45 knots

- A maximum seating capacity of no more than two occupants

- A single, non-turbine engine fitted with a propeller.

- A non-pressurised cabin

+ FAA added the following more restrictive criteria (because their goal is to keep the aircraft simple)

- Max. Speed in Level Flight must not exceed 120 knots

- Propeller must be Fixed-pitch or ground adjustable

- The single engine must be reciprocating (piston engine, they did this to exclude turbine engines but accidentally excluded electric motors)

- Landing Gear fixed (except for seaplanes and gliders)

Both regulators have restricted operations to VFR. EASA allows night VFR if approved by the manufacturer.

The two approaches

The FAA approach has been to create two categories for LSA aircraft, Experimental Light Sport (ELSA) and a Special Light Sport (SLSA). ELSA aircraft are built from kits or plans by the owner and SLSA are factory built. ELSA aircraft could only be used for private use while SLSA aircraft could be used for hire and instruction. Certification of the SLSA was to be done by Industry consensus rather than direct FAA oversight. The result has been a healthy and growing LSA segment in the USA. (696 LSA aircraft sold in 2019)

The EASA approach has been a lot more conservative. They have created a new certification category called CS-LSA. Even though the process is lighter than the traditional CS-23 and CS-VLA certification, it is still fully supervised by EASA. Out of all the designs that comply with the above definition and restrictions (more than 150 models), only half a dozen have gone through the cumbersome EASA certification process. This process has added an estimated €30,000 – €50,000 of additional cost per aircraft sold. On top of the airframe certification there is a requirement that all equipment is fully certified which adds further cost. (non certified equipment can be certified as part of the aircraft but this has its own burdens for the manufacturer).

The output of the process is a fully Type certified EASA aircraft that can be used the same as any other General Aviation aircraft within its specified limitations. Great for getting slightly cheaper and more modern General Aviation trainer aircraft on the market but a far cry from the goal of LSA to expand recreational use of the aircraft.

Note: Even if a EU member country has opted-out to allow 450 – 600 kg Ultralights, a manufacturer of that country can still opt-in with their aircraft design and obtain the EASA CS-LSA certification.

Experimental Aircraft

EASA puts ultralights under National rules as mentioned above. All Ultralights in Europe are considered experimental by definition. Those that are factory built will be registered as Ultralights and entered into the national registries. Kit built aircraft that meet the EASA definition of an Ultralight are given a national permit to fly providing they meet quality and design requirements. The Assessment is done by a member state regulator (Traficom in Finland). If aircraft fall outside the Ultralight definition they usually obtain a permit to fly as a SEP (Single Engine Piston) aircraft.

With the exception of factory built ultralights that can be used for training and hire, experimental aircraft can only be used for personal recreation or research. The rights of Ultralights and other SEP experimental aircraft to leave their national airspace must be separately agreed between member nations.

The FAA has a similar approach with the only difference being that kit built aircraft that fit under the LSA definition become ELSA and others that do not become E-AB (experimental amature build) aircraft. The FAA puts a lot less restrictions on E-AB aircraft compared to EASA. For example EASA do not allow IFR flight for Experimental aircraft regardless of whether the aircraft has the needed equipment or not.

Licensing differences and Medical requirements

EU member states are allowed to have their own national licenses and requirements. EASA has developed a LAPL (Light Aircraft Pilot License) with the idea of harmonizing standards for Light Aircraft training. The LAPL is easier to obtain (30 hrs flight time) than a standard PPL (45 hrs flight time) but has more restrictions. Another key difference is that a LAPL licence does not have a SEP Rating like PPL licenses do but requires endorsements for the aircraft which the holder wants to fly. LAPL license holders can upgrade to a PPL with additional theoretical study and flight training. PPL holders need 2 hours differences training to fly Ultralight aircraft.

Flying recreational aircraft in the EU requires a pilot to have at least a valid LAPL medical certificate if flying LAPL specific aircraft. This medical can be given by a normal GP and is slightly less demanding than a Class 2 medical certificate. If a LAPL pilot is flying SEP aircraft they need to hold a Class 2 medical certificate or higher.

The FAA requires a student pilot licence which is not required in Europe by EASA. As stated above, the FAA does not require licenses to fly vehicles that fall under the FAA definition of an ultralight. A Sport Pilot License was introduced in 2004 for those pilots that only want to fly LSA aircraft. Training requirements for this license are minimal (20 hrs flight time) and only a drivers license medical or higher is required. There are however strict restrictions on the conditions and airspace pilots can fly in.

There is an older Recreation Pilot license available which more closely equates to the EASA LAPL but has more restrictions and requires a Class 3 medical certificate. Requirements for a PPL are very similar to EASA. More information on FAA licensing can be found here.

Differences in Logging Hours

In the USA, Ultralights under the FAA definition are not considered aircraft so in accordance with 14 CFR Part 61.51 the hours do not count towards PPL SEP hours. All other hours in accordance with Part 61.51 flown in LSA aircraft, Experimental aircraft and Certified aircraft count towards SEP hours.

In Europe, Ultralights hours must be kept in a separate Ultralight logbook but can now be used towards renewing a SEP Rating. Hours that are flown in any EASA certified aircraft (CS-23, CS-VLA, CS-LSA) or Annex 1 experimental aircraft with a non Ultralight registration (e.g. OH-XRH in Finland), can be logged as SEP hours and used toward renewing a SEP rating.

Final Thoughts

The USA has benefited from lighter regulation around Light Sport Aircraft that has made recreational flying more affordable and accessible. Even though training and medical requirements have been lowered, statistics show that there is still a satisfactory level of safety. In addition, the LSA category has been implemented in such a way that it does not create a divide between PPL SEP pilots and those flying LSA (or what would be deemed ultralights in Europe). So all in all, well done FAA. (interesting video on LSA safety from Avweb)

New EU rules for Ultralights up to 600 kg introduced in 2020 are well overdue and will benefit the growth of the Ultralight category. By doing this though, EASA has drawn a very big line in the sand between PPL SEP aircraft and Ultralights which in practice means pilots will probably end up choosing to fly either Ultralights or SEP aircraft. Fortunately at least now the Ultralight hours can be used to renew a SEP rating.

The EASA process for certifying LSA aircraft is still too cumbersome and costly for manufacturers given the small number of planes they produced. More needs to be done to remove this barrier and make certification affordable so that more pilots can enjoy cheaper recreational flying.